When we talk about racism, some people say, “You’re an insurance company. What does race have to do with anything?”

It’s a good question, and the answer is: a lot.

Some people may be surprised to find out how much race impacts health. For example:

Black and American Indian women are up to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.1

African Americans have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension and heart disease than white Americans.2

American Indian populations face a 60% higher infant mortality rate than their white counterparts.3

Hispanics are less likely to have health insurance than non-Hispanic whites.4

Hospitalization and death rates due to COVID-19 are 1-3 times higher for Black, Asian, Hispanic and American Indian people compared to non-Hispanic whites.5

Why? It’s complicated.

Sometimes people tell us it’s a matter of personal choice. If you don’t take care of yourself—eat right, exercise, follow the doctors’ orders—you’ll experience poorer health.

It’s true that individual behavior influences your health. But a wealth of research shows us that individual choice alone doesn’t explain these racial disparities – and neither do biological differences among racial and ethnic groups.6

So what causes racial differences in health and health care?

Many factors can influence health: your zip code, your income level, whether you have access to healthy food and reliable transportation… The list goes on.

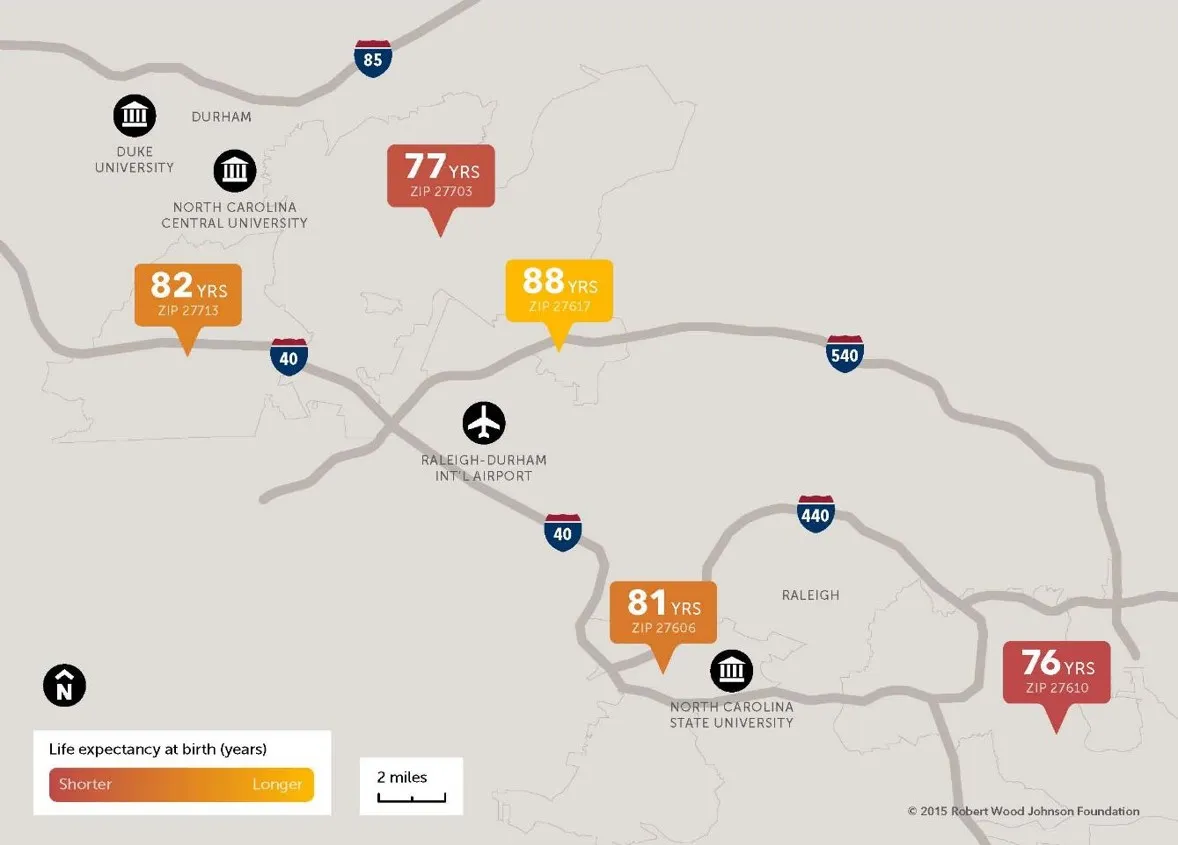

These social economics factors have significant impact on people life expectancy. The map below shows life expectancy varies by more than 12 years depending on which community you live in the state of North Carolina.

At Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (Blue Cross NC), we call these “drivers of health.” And we are intentional about addressing them in communities that are impacted by long-standing bias and discrimination.

We can look at socioeconomic status as an example.

Across the United States, 39% of African American children are living in poverty. This makes Black children more than twice as likely as white children to be living under the poverty line.7 And according to the American Psychological Society, that sets those children up for poorer health in the long run, by no fault of their own.

What does racism have to do with it?

If we take this example a step further, we can look at what causes poverty. The United Nations counts racism and discrimination among the top causes of poverty worldwide.

We often see this play out, for example, in the hiring process. A study by an economist and a behavioral scientist found that resumes with white-sounding names received 50% more callbacks than those with Black-sounding names.8

“All other things being equal, race is still an important factor in the American labor market,” the authors note. “A black applicant’s race certainly has negative effects on their employment prospects on average.”

Systemic racism and other forms of discrimination drive these negative effects. And implicit bias, or attitudes we have toward groups of people without consciously realizing it, isn’t just present in the hiring process. It also shows up in health care settings.

Bias in medicine

We all have bias. It can stem from our family upbringing, schooling, culture, movies or literature—including medical textbooks.

Have you ever been told that Black people have thicker skin than white people? Or that Black folks have less sensitive nerve endings than white folks? Neither one of these claims is true. But many people, including medical students and residents, still believe them.9

Studies show many doctors have a significant pro-white bias and unconsciously associate Black patients with being less likely to cooperate with medical procedures. As a result, Black patients often receive different treatment than white patients:10

They may receive lower quality of care

Their doctors might not communicate with them as frequently or clearly as with white patients

Their doctors may be less friendly toward them

They may receive less pain medication than white patients in the emergency room

They may be offered different treatment options than white patients

The good news is most doctors and nurses want to provide the best quality care to all patients. And we can all challenge our implicit biases.

What can we do about it?

As part of our efforts to challenge bias in health care, we’ve invested in implicit bias training through March of Dimes. The organization has offered trainings to medical professionals across the state to help them gain insight to recognize and remedy implicit bias in maternity care settings.

At Blue Cross NC, we need to understand our own implicit biases, too. That’s why we provide implicit bias training and other learning opportunities for our employees. We encourage everyone to take the 21-day racial equity challenge.

And training is just the start. Racism operates at many levels, from person to person within our institutions. That’s why we’re also building on our strong culture of diversity and shifting to value-based care. Our goal is to create fair opportunities and inclusive spaces for everyone to have good health and well-being.

As a not-for-profit health insurer, we know that no community can truly be healthy until racism no longer exists. Health inequity impacts all North Carolinians. In fact, data shows our state’s health system ranked #36 out of 50 states. We also ranked #46 out of 50 for disparities.11

Addressing these disparities and inequities makes health care better—and less expensive—for everyone. We’re committed to supporting communities all across the state. We work collaboratively with our providers, members and communities to transform health care delivery through value-based care. We won’t stop until health care is better for all.Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and the strength of our communities are at the heart of everything we do. To learn more about our commitment to DEI, visit our website.

Ready to get started?

Related Articles

Blue Cross NC Statement On Racism

We stand with our Black employees and members along with all others who are experiencing trauma as a result of the ongoing violence against Black lives in our country.

Blue Cross NC

Struggle, Progress & Strength: Recognizing Black History Month At Blue Cross NC

Progress can be a complicated thing. The non-linear process of it, the perceived need, the actual need, the expectation of it and the experience of it vary. It looks different from person to person, organization to organization and community to community. For some, progress is a scary thing. It can threaten comfort zones and the status quo. For others, progress is as important as air and is needed for survival.

This concept of progress and the different meanings it holds can apply to almost any aspect of our lives. We seek progress in health and wellbeing, personal relationships, workplaces, and communities and systems in which we live and operate. And champions of progress can seek it for personal aspirations, or for a greater, much larger purpose, “lifting as they climb,” as Mary spoke.

Archele Moore via Blue Cross

“I Can't Breathe": Racial Injustice & Black Mental Health

Fast forward to March 2020. We found ourselves in a worldwide pandemic. Many of us felt this year couldn’t get any worse. But 2020 stood up, stretched, and said, “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet. I’m just getting started.”

May 25, 2020. George Floyd was murdered, and the whole world watched in horror. This isn’t the first Black man killed unjustly on video. But for many people, this felt different. This was a slow, painful execution. We watched this man as the life slowly left his body, the knee of an officer on his neck. Unapologetic. No remorse. Even as the Black man pleaded and begged, “I can’t breathe. Please. I can’t breathe.” Then, on instinct, he cried out for his mother to save him.

Brian Edmonds